But now they were all hurtling toward the forest canopy.

“I have a river to my right,” Murcia said, according to a preliminary crash report. “I’m going to touch down on water.”

He never made it. The Cessna U206G Stationair hit the trees, broke apart and plunged nose-first to the forest floor. When Colombian special operations soldiers reached the wreckage two weeks later, they found three bodies. Mucutuy, Murcia and a third adult were dead. But there was no sign of the children. The collision had barely damaged their seats — and the discovery of a diaper, a half-eaten piece of fruit and small footprints sparked an unreasonable hope: Could they still be alive?

Even in this country of magical realism, it was difficult to imagine. Family members believed the children might have the skills to survive in the jungle. But this was a notoriously dangerous stretch, infested with jaguars and venomous snakes.

Finally, after more than five weeks of searching, came the miracle: The children were found alive. Even baby Cristin, who’d turned 1 in the forest.

They had survived the seemingly impossible. First, the plane crash that had killed all the adults. Then 40 days in the most inhospitable of environments.

But their battles, it would turn out, were far from over.

The travelers were midway through their 95-minute flight on May 1 when the plane vanished from tracking systems. The search began immediately, with a days-long walk into the forest. A team of six Indigenous men led by Edwin Paky, 36, swung machetes to hack a path through the virgin forest, making slow progress toward the crash site.

They knew the forest well enough to be confident. But also well enough to be wary.

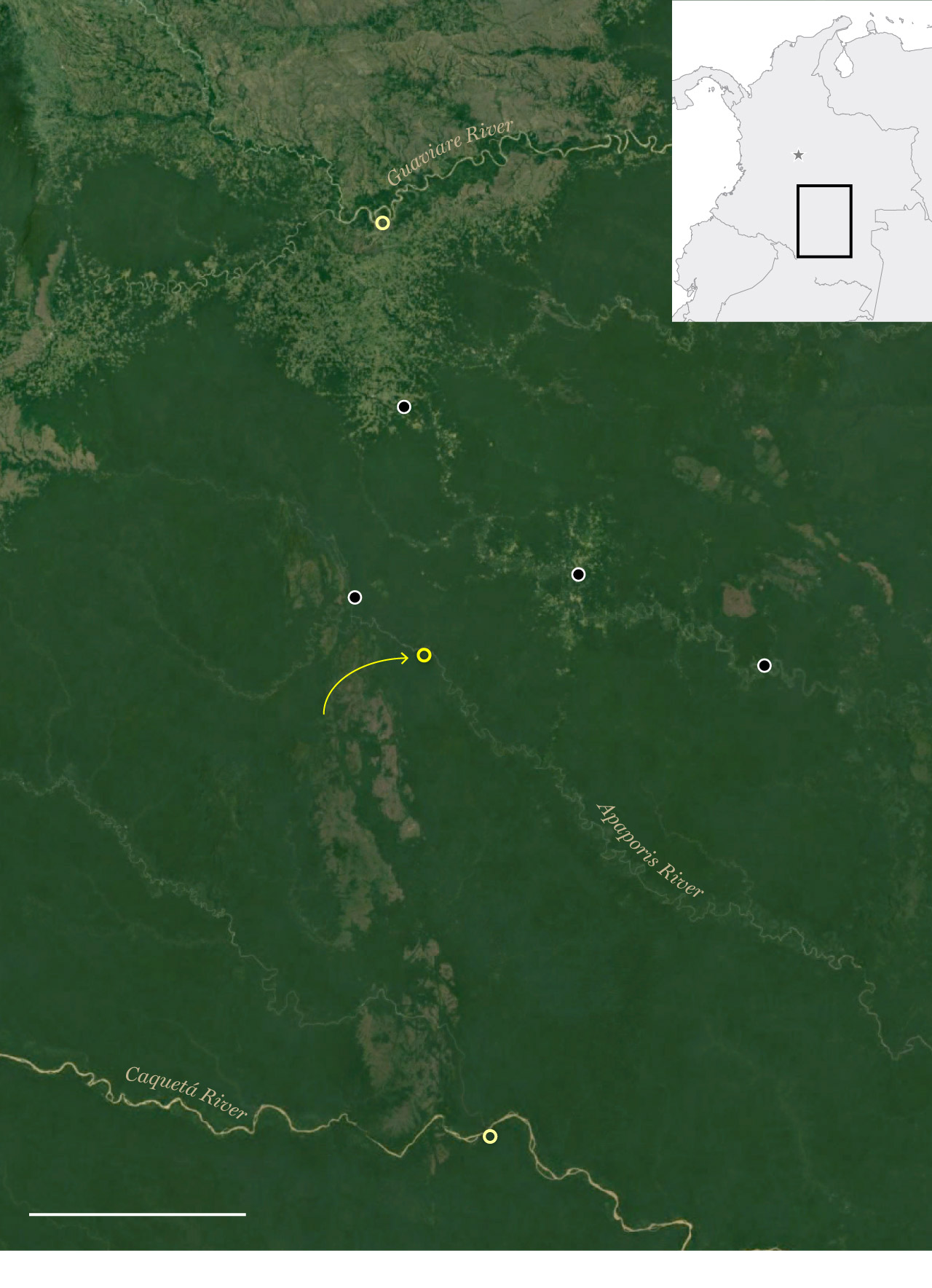

This was one of the densest, wettest, least explored corners of the Amazon basin, an interlude wedged between the Caquetá and Apaporis rivers in southern Colombia. The air was humid; the terrain, sodden.

Caribbean Sea

Destination

of plane

San José

del Guaviare

Miraflores

Plane crash site

May 1 at approx.

7:44 am

Children discovered

2 miles from crash

Plane departs

Araracuara

May 1 at 6:42 am

Sources: Post reporting, Colombian Government,

Landsat imagery via Google Earth

Caribbean Sea

Pacific

Ocean

Destination

of plane

San José

del Guaviare

Miraflores

Plane crash site

May 1 at approx. 7:44 am

Children discovered

2 miles from crash

Plane departs

Araracuara

May 1 at 6:42 am

Sources: Post reporting, Colombian Government,

Landsat imagery via Google Earth

Caribbean Sea

Pacific

Ocean

Destination of plane

San José del Guaviare

Miraflores

Plane crash site

May 1 at approx. 7:44 am

Children discovered

2 miles from crash

Plane departs Araracuara

May 1 at 6:42 am

Sources: Post reporting, Colombian Government, Landsat imagery via Google Earth

But the terrain wasn’t merely uncomfortable; it could be dangerous. In the years since the historic 2016 peace deal that ended a half-century of conflict between the paramilitary Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia and the government, a sense of optimism had given way to apprehension and resentment. The FARC had been largely dismantled. But the government had been was slow to make good on its end of the deal: Measures to relieve poverty in conflict-torn rural areas that had long suffered state neglect. Old guerrillas were rearming; new groups were mustering.

The result: A region now “complex and extremely insecure,” said Carlos Lasso, a security analyst at the Alexander Von Humboldt Biological Resources Research Institute in Bogotá.

Days into the search, Paky injured his knee. He was limping behind the others when he heard the shout: “The plane!”

The fuselage of the shattered aircraft stuck out of the ground like stalagmite.

Approaching, they could smell the bodies. Inside the cabin, they found Murcia on top of Mucutuy, both dead. As was the third adult, the Indigenous leader Herman Mendoza Hernández. But they also noted also signs of life: The plane door was open. Several bags had been brought outside. An improvised camp — little more than a bed of twigs — lay near the wreckage.

To Paky, it was obvious. The kids were alive.

A survivor at age 13

A phone rang in Bogotá. A gaunt black-haired woman received news that filled her with anguish, but also hope. María Fátima Valencia’s missing daughter had been found dead. But her grandchildren were still unaccounted for. Searchers and officials believed they had wandered into the forest.

At home in their Indigenous community near Araracuara, Valencia, 63, saw the children nearly every week. She knew they were strong. They had to be — they lived in a region of Colombia almost entirely disconnected from the central government. No cell service. No electricity. No roads. The only means of travel? Walking paths and rivers. The nearest highway took three hours by boat and three more on foot.

“It’s very difficult,” she said.

“A place the state has completely forgotten,” said Manuel Miller Ranoque, Mucutuy’s husband and the father of her two younger children.

Lesly, the oldest child, was raised to survive. Like other Huitoto children, she knew from a young age how to walk in the jungle, fish its waters, which fruits to eat and which to avoid. At 13, she lived as an adult. While her parents worked, she cared for her younger siblings and cooked, her responsibilities left her little time for mischief or mirth.

“A very smart girl,” Miller said. “Very serious. Short-tempered. Responsible.”

If anyone had the strength and cunning to survive the jungle, her family believed, it was Lesly.

‘My God, what is this?’

Gen. Pedro Sánchez was less sanguine. The head of Colombia’s Special Operations Joint Command, he was admired for his competence and organizational capacity. But he had never taken on a mission like this.

It was dubbed Operation Hope. It had taken the first searchers more than two weeks to locate the plane— but that was only the beginning. From there, they calculated how far the children might walk in a day to establish a search perimeter. Its size was stunning: More than 160 square miles, in a forest so dense that visibility was less than 60 feet. And so wet it would rain more than 16 hours per day.

Most daunting of all, the children were moving targets. They’d have to comb the same quadrants repeatedly.

“This was my most difficult, most complicated mission,” he said. “Supremely complex.”

His team needed to invent new methods of search. They strung up lines of construction tape with whistles attached so the kids could signal them. They set up a loudspeaker and a large light to orient the rescuers and save them from getting lost themselves. They determined that sound carried more than 2 miles, so they blasted a message, recorded by Valencia in their Indigenous language, telling them to stay put. And they dropped food they hoped the children would find.

Within days, nearly 200 responders — a mix of Colombian special operations and Indigenous volunteers — had ventured into the forest. Sánchez was encouraged. They had found evidence of the children. The diaper and the top of a baby bottle were uncovered near the crash site.

By May 20, Sánchez was convinced they were close. They’d found footprints. He told his superiors they were hours from finding the kids. Then a massive rain drenched the forest. The footprints were washed away. The trail was lost.

“My God,” Sanchez remembered asking: “What is this?”

Lost and alone in the forest

Lesly knew her mother was dead. Mucutuy was lying motionless. So were Murcia and Mendoza. But elsewhere in the wrecked cabin, her siblings were stirring. She pulled her baby sister from her mother’s arms and brought her other siblings out of the wreckage, she told her grandparents. She held one of her brother’s diapers to a gash in her head, her grandparents told The Washington Post.

Outside the plane, Lesly set up a basic camp, stringing a towel and a mosquito net to provide shelter, and settled down to wait. They stayed for a long time — perhaps one day, maybe more. At one point, she told her grandparents, her younger brother asked when their mother was going to wake up. Lesly, uncertain whether he understood their mother was dead, said she didn’t know.

With no help coming, Lesly said, she decided to leave the wreckage. She had been taught the importance of a water source. So she gathered all the provisions she could find: 11 pounds of the yuca flour called fariña, a pair of scissors, the mosquito net and the baby’s bottle. Then the four children set out in search of a river. For shelter at night, they relied little more than a webbing of branches strung overhead.

The forest didn’t scare Lesly, she told her grandparents. Nor did its animals. But now it was strange. She heard her grandmother’s disembodied voice — the searchers’ broadcast — but didn’t understand. Was Valencia in the helicopter she saw passing overhead? She made out other voices in the forest, but was nervous to go to them. She was afraid she’d be punished for leaving the plane site. To muffle the baby’s cries, she put a hand over her mouth.

They didn’t have much food. Lesley rationed baby Cristin’s milk. When it ran out, she dropped the empty bottle onto the forest floor. Her siblings complained of in their abdomens. The children found some of the food dropped by the searchers and foraged for seeds and fruits. But it wasn’t enough.

As hunger was closing in, the children’s time was running out.

‘Those are the children!’

The Indigenous scouts prayed to the spirits of the forest. They had taken the hallucinogen yagé, in the hope it would give them the vision to find the children. They had been injured, sickened, depleted. On the 39th day, many were ready for a break.

But two men, Dairo Kumariteke and Eliécer Muñoz, felt confident. One of the elders had taken yagé and seen the children in a vision.

Then came the faint sound of a baby crying. The searchers stopped and listened.

Another wail.

“I think those are the children!” Kumariteke said, he later told reporters.

They rushed toward the sound. And then there they were — dirty, skeletal, weakened, but alive. Lesly was holding Cristin, now 1. Nine-year-old Soleiny stood beside them.

It was June 9. Forty days after the crash.

“Tenemos hambre,” Lesly said. We’re hungry.

They found the last child, 5-year-old Tien, lying on the ground 50 feet from the others.

“My mom died,” he said.

“But your grandmother is looking for you,” one of the Indigenous rescuers said. “We’ll take you to her.”

A battle for custody

Fátima Valencia and Narciso Mucutuy, Magdalena Mucutuy’s parents, caught up with their grandchildren at a military hospital in Bogotá. It was soon mobbed with press and officials. Another battle was already beginning to take shape, this one for control of the narrative — and the children.

Two camps had formed.

On one side was Magdalena Mucutuy’s husband. Miller had participated in the search. Outside the hospital, he told reporters that an armed group had been trying to recruit the older children and had threatened his life. To escape the threat, he’d wanted to bring the family to the capital.

After the crash, he said, his wife had lived for four days. In her dying words, he said, she told the kids to find their father.

Miller said his family, not his in-laws, should take care of the children.

“They didn’t grow up next to the grandmother,” he told The Post.

On the other side were Mucutuy’s parents. Mucutuy and Miller had shared a combustible, unhappy union. Now her parents called their son-in-law an abuser and a liar.

Narciso Mucutuy told Colombian media that his daughter had died immediately. He said Miller was a violent person and alleged he’d struck his daughter. At times, Mucutuy said, the children hid in the forest while their parents fought.

Miller, asked by Colombian media if he attacked the children’s mother: “Verbally, yes. Physically, very little. We more fought with words.”

To The Post, he said: “Yes, we mistreated each other verbally, but I never left her in bed for hours or days because of some beating I had given her.”

After the crash, Fátima Valencia filed a police complaint against Miller alleging domestic violence. She blamed him for her daughter’s death. Security in their Indigenous community wasn’t as bad as he claimed, she said. There had been no reason to flee to Bogotá. The kids had been safe at home.

Miller cast his in-laws as oblivious. “They’ve never worried about anything,” he told The Post. “How are they going to fight for custody of the children?”

The sides set their differences aside for a moment Wednesday morning in the hospital. Fátima Valencia had fallen ill after seeing her grandchildren and was admitted to the hospital. Now she was on the phone, talking to the kids. Her voice was quiet, nurturing.

“Don’t be sad, because you’re with me, my girl,” she told Soleiny. “You’re beautiful, my precious.”

She asked for Lesly. The girl’s voice was low and flat.

“Oh, my girl, don’t be sad,” the grandmother cooed. “Don’t think of anything. Just stay there and eat, sleep, rest. All right?”

Marina Dias contributed to this report from Brasília.